The monkey’s lawyer threatened swift and decisive action to defend his client, which upon reflection forced me to question a lot of decisions I’d made in my life up to that point.

But enough about the monkey and his attorney for now. Let me digress a moment and tell a story that has a happier ending and holds a lesson for people in business and who have plans that need to be implemented in the real world:

For the cost of an extra wing nut, you can save both yourself and your own moral equivalent of the Space Shuttle Challenger – just as long as you make the investment before you launch.

Whether you’re managing disaster preparedness and response at BP, ensuring you’ve got extra aces up your sleeve for your global product launch or just making sure you never get a phone call from an attorney representing a non-human, planning for what happens when the worst case scenario unfolds is the discipline that separates the professionals from the cowboys.

Here’s a coming of age story – told in the first person, regrettably – that brings this point home.

The US Olympic Committee Sees Nothing Funny in My Stuff.

The Atlanta Summer Olympics of 1996 was a model of heavy corporate involvement, the Die Another Day of Olympiads. Everything that could be stitched, labeled or plastered had an official sponsor. The fact that the Games were held in the US Olympic Committee’s home town probably had an influence on this.

Brands – those global behemoths that had the extra millions for a dubious ROI ego trip, that is – snapped up any and all rights possible. Panasonic, as I recall, had category exclusivity for consumer electronics.

But I, sitting in my cubicle as Director of Marketing for the consumer media division of rival Sony, had a clever idea that would leverage the billions of other people’s dollars for my own purposes.

Cast your mind back to the mid-1990’s. If you were in any sort of consumer packaged goods world back then, promotional phone cards were the currency of the day. And we played in that game heavily. With 33% of our volume going through Walmart and a consumable product closer to soap that Trinitrons, we were in the CPG business. We had ironed out the phone card industry to the point that we had 10 minute cards for less than $0.24 each, including manufacturing costs, where our competitors were paying upwards of $1.50.

So with the Olympics bearing down on us, I signed individual contracts with former Olympians Bruce Jenner, Matt Biondi, Julianne MacNamara, Karch Kiraly and Frank Shorter and secured the rights to use images of them appearing in non-Olympic events which we would use on our in-packed phone cards.

We would stack them to the rafters in the Walmarts, Targets and Kmarts from coast to coast. We secured the ads and the endcaps. We had a way to get where we wanted to go. Sony legal was happy, management was happy and I was happy.

Even Brandweek thought it was fun. So fun that they ran our promotion as a cover story. “Sony Looks to Dial Up Olympic ‘Ambush’ With Phone Card Deal.”

And thanks, Brandweek, for calling it an “Ambush.”

Apparently, Brandweek’s take didn’t sit too well with the US Olympic Committee, whose letter to Mr. M. Morita crushed my management’s resolve like the space station MIR landing on a double-wide trailer. It ended up with me, as you can imagine. “Kill it… kill it quickly,” were my instructions. Big companies can be like that.

Major League Baseball and Strike Two.

I killed it, turning to Major League Baseball, only to learn that MLB was owned by the owners and the MLBPA – the Player’s Association – was run by the player’s union. You can show a player, but you have to photographically obscure his uniform. If you want him in his uniform, you have to pay both parties. Forget it. I’m not putting pinstripes on Big Papi. And life is too short to have to negotiate all of these contracts, particularly with a legal team that ducks like an extended family of meerkats when they see me coming.

The Damn Monkey. And His Lawyer.

I know. I’ll use images from Sony’s own advertising campaigns of years past. Like the famous snow monkey they used for the launch of the Walkman. Thus, the call from the monkey’s lawyer. Apparently, Sony didn’t own the rights to this and since that time, the monkey – the monkey – has become a huge celebrity. In Japan, of course. Where monkeys can become huge celebrities, apparently. We could not use his image. Or we’ll get sued by the monkey.

I ended up using a series of images developed by the Sony Design Center that were based on our admittedly beautiful packaging designs and that required no one’s approval but mine. We sold it all in to the channel, they put it up on the end caps and hit it with circular advertising and it sold through just fine.

I physically crushed one of those sand filled squeeze balls in the midst of all this. Got all over everything.

“An Awful Lot of Information is Transmitted by the Kick of Mule.”

And the thing is, I didn’t have to go through all this anguish.

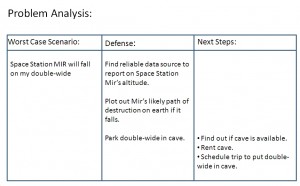

What I learned from this and have successfully put to use ever since is a simple method of isolating and managing risk in projects. I learned this in a nameless seminar from years ago and the format has changed many times since, but this is basically it:

Paint your worst case scenarios in column A. “The Space Station MIR will fall on my double-wide.” List them all out. Assign what you think is appropriate for likelihood and severity.

In column B, describe what you can do ahead of time to avert your worst case scenario. “Find reliable data source to report on Space Station MIR’s altitude.” Add, “Plot out MIR’s likely path of destruction on earth if it falls.” You could include, “Park double-wide in cave.”

Next to this, list the things you need to do – now – to ensure you can do what you need to do in column B. “Find out if the cave is available,” for example.

Key Takeaways:

Think about this for a moment – how much time would an analysis like this really take? Is this a few hours of your and your team’s time?

What does it sign you up for that you’d prefer not to have in hand anyway? How much stress would be eliminated if you knew that no matter what your negotiating opponent had to say, you had a viable alternative in your back pocket? Would this confidence impact the non-verbal cues you’d be giving off during negotiations?

Would your management, your shareholders – your wife – feel a little more comfortable with your decision (not to mention how easy it is to live with you if it is your wife we’re talking about) if you had this level of contingency planning in hand on a major launch?

* * *

Knowing what the likely O-rings were in various programs and having the alternative lined up became standard operating procedure from that moment on. I’ve rarely had programs that had cascading problems like this one, but it was instructive as hell. So please learn from it. It isn’t hard to fix ahead of time.

Put yourself in BP’s shoes for a moment. If your company was pulling down $20 billion in profit a year, do you think that shaving off $20 million or so to create a deep water disaster team, actually doing training missions down that far in those conditions, would have been a good insurance policy? A little late now, but a suitable cautionary tale nevertheless.

Regards.

[…] the original post: Shutting Up the Monkey's Lawyer: Avoiding the #1 Pitfall in … Posted in […]

Stephen, enjoyed this column. This kind of risk management enabled via scenario planning is all too uncommon in marketing management. We’re taught to optimize, strive for efficiency and lay our best plans, with anything else considered a waste of time and money. Adaptability and agility will be the new buzzwords for marketers in an ever shifting global world. Financiers hedge their risk without a second thought. Perhaps it will soon be second nature for marketers as well.

Paul: thanks for your comment – there’s a likely answer to this question on why marketers frequently skip this important step, and it dovetails in with recent discussions with others (@TedCoine and @ThomasLanen on Twitter), namely that marketers are often so focused on not making mistakes that they keep their programs as simple and “idea-free” as possible. They prefer (often, not always) the mental security of measuring more than the risk of creation.

As mentioned up on Twitter, an over-reliance on the science is little more than institutionalized “CYA,” characterised by marketers too timid to really step out and do something game-changing. And, in fairness, those to abandon the science for a pure-play “art of marketing” are usually exercising little more than self-indulgence. Both are required. But if we choose to push beyond the obvious and “do things” – not always the case with marketers and brands themselves – let’s give planning and disaster preparedness its day and acknowledge the right tools that will keep you safe from the simian and his legal defense team.

Thanks, as always – appreciate your stopping by!

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by StephenDenny, StephenDenny. StephenDenny said: Shutting Up the Monkey's Lawyer: Avoiding the # 1 Pitfall in Project Planning. http://bit.ly/a1Ppsl [I still get that facial twitch …] […]